By Shonda D. Gray

link to the corresponding oral history: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Weh64Rp-V-I&feature=youtu.be

City Hospital No. 2, public hospital for African-Americans only was built in Mill Creek Valley, a black community in St. Louis City during a time of segregation. City Hospital No. 2 was built in 1919 to address the limited access African-Americans had in medical care, and medical educational training. The former Barnes Medical College, City Hospital No. 2 sat on Lawton and Garrison, it was one of the three hospitals in St. Louis City that serviced African-American patients as well as taught African-American medical students.[1]

With City Hospital No. 2 being such a small hospital with 177 beds, there were two additional private hospitals that serviced African-Americans; St. Mary’s Infirmary, located on Papin and 15th Street, south of downtown, and Peoples Hospital, a private three story building located on Locust in downtown west area. At Peoples Hospital, “patients had to pay out of pocket to receive medical treatment due to it being a “private” hospital,” Mary Covington stated during our interview.[2] Ms. Mary Covington, made it known to me that, her mother had to pay to give birth to my younger brother at Peoples. Mary Elizabeth Covington, 81 year old St. Louis City resident, was born at City Hospital No. 2 on January 5, 1936. She was the oldest of twelve siblings that were all born at City Hospital No. 2 during the segregation time in St. Louis City. Mary made it known to me that her family took great pride in their community, even though segregation was strongly enforced. “We knew what hospitals to go to, and what streets we could not go pass,” Mary stated.

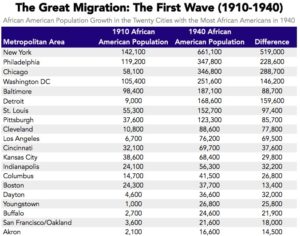

The need for hospital care was scarce for African-Americans between the years of 1918-1937. City Hospital No. 2 was looked at as an inadequate hospital. The quality of medical service was poor, along with poor building conditions. The previous Barnes Medical College was in poor conditions when it was deemed City Hospital No. 2 by St. Louis City government officials. All during a time when the population of African-Americans significantly increased in St. Louis due the “Great Migration.” African-Americans from Southern states began to migrate north coming into St. Louis, Chicago, and New York. As the migration was happening, many decided to settle in St. Louis. The migration took place between 1916-1970.[3] According to the Census Report, from 1910-1940 approximately 98,000 African-Americans were living in St. Louis City that would have to be serviced by a hospital that only had 177 beds for patients.[4]

Data: Census

The increased number of the African-American population in St. Louis City caused a push for a larger quality hospitals for African-Americans. In 1922, Homer G. Phillips, an African-American Attorney and Advocate pushed to have St. Louis City government officials to build a larger, more sufficient quality hospital for African-Americans that would both service patients, and medical training for African-American doctors and nurses. As my co-author, Terri Williams discussed in her paper, Phillips had to fight hard with state and government official to pass a Bond that would cover the cost of the new City Hospital No. 2. One million dollars of this Bond money was allocated to the new African-American hospital that opened up in The Ville Neighborhood, north of The Mill Creek Valley Neighborhood, where the once City Hospital No. 2 resided. The new City Hospital No. 2 was opened and renamed “Homer G. Phillips” in 1937. [5] The government officials wanted the next City Hospital to be far away from the Darst-Webbe location, hence how the next location for City Hospital No. 2, was constructed in the Ville neighborhood. The Ville neighborhood was the new vibrant and upcoming African-American neighborhood. Especially since it seemed that the African-American from Mill Creek Valley Community was being pushed north for political and business interest of the land where the majority of St. Louis City African-Americans resided, and conducted business. The demolition of Mill Creek Valley in 1959, generated the shift of African-Americans in St. Louis City to migrate north within St. Louis City. African-American residents that were displaced and uprooted from the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood moved north and to the Ville neighborhood. Mill Creek Valley and the Ville were two areas in St. Louis City known for its great African-American culture. By this time, segregation in St. Louis was prevalent. It forced African-American to build a culture of oneness in such a quickly changing environment. They created a since of belonging during a time of great racial inequality by reestablishing themselves. They built community once again by having their own hospitals, schools, businesses, and theaters. Look at how quickly things have changed or not have changed.

In conclusion, racial segregation, legal orders, restrictions-the use of restrictive covenant pushed African-Americans further north from the Mill Creek Valley Neighborhood, leaving one to believe placing the hospital in The Ville neighborhood would get more blacks to move in that area. Political interest and downtown business influence manipulated and forced to have the Mill Creek Valley area blighted and cleared in 1954. The hospital move in 1937, would lead one to believe that the Redevelopment Plans for Mill Creek Valley were in talks years prior to its demolition.

The current utilization of space and the environment is different and erupted from what it was back in the 1920s-early 1950s. The original City Hospital No. 2 on Lawton and Garrison no longer exists. It was demolished in the 1960s. The street Lawton no longer exists where it once sat. St. Mary’s Infirmary was demolished in 2016 where is sat on Papin and 15th Street. The street has been renamed and dedicated Papin and St. Mary’s Infirmary Nurses. Peoples Hospital remain vacant and sitting on Locust between Lofts. None of these sites have not been recognized for its rich history for providing medical services to African-Americans prior to Homer G. Phillips being built in 1937.

Footnotes:

[1] “Mound City on the Mississippi a St. Louis History.” St. Louis Historic Preservation. https://stlcin.missouri.org/history/structdetail.cfm?Master_ID=1578.

[2] “City Hospital No. 2 with Mary E. Covington.” Interview by author. April 29, 2017

[3] “The Great Migration-Black History.” http://www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration.

[4] Kopf, Don. “The Great Migration: The African American Exodus from The South.” Priceconomic.com. January 28, 2016. https://priceonomics.com/the-great-migration-the-african-american-exodus/.

[5] Joiner, Robert . “St. Louis struggles with its promise to take care of the poor.” Http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/st-louis-struggles-its-promise-care-poor#stream/0. October 14, 2010. http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/st-louis-struggles-its-promise-care-poor#stream/0.