By Julie Flory and Sean Gunsten

The clearing of St. Louis’s Mill Creek Valley Neighborhood in the early 1960s at the time probably felt in many ways like the end of an era. When the 465-acre parcel was razed, city leaders congratulated themselves on their success – they had “cleared the slums,” as they had promised their constituents, transforming the city’s “No. 1 Eyesore” into a wasteland that would come to be known as “Hiroshima Flats” (O’Neil). Mayor Raymond R. Tucker promised a new beginning, and while, for much of Mill Creek Valley, his vision did not materialize in a lasting or meaningful way, at least one section did rise from the ashes to survive – and even thrive, if only for a relatively short time.

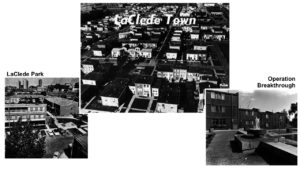

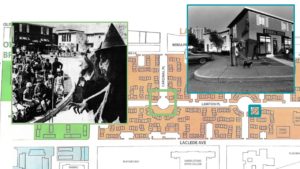

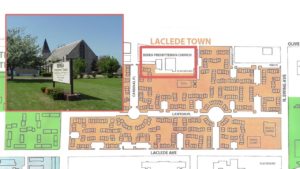

LaClede Town was a public housing development like no other. From its socially inspired design to its virtually hand-picked clientele, it was by most accounts a successful experiment in bringing together a diverse – and frequently eclectic – assortment of residents, including many artists, musicians, and activists, living together in community, in the truest sense of the word. Located in the northwestern-central section of the Mill Creek Valley clearance area west of downtown St. Louis and north of Highway 40, LaClede Town’s primary boundaries were Olive Street to the north, Ewing Avenue to the east, LaClede Avenue to the south, and Compton Avenue to the west.

LaClede Town partially opened in 1965 with 285 units, then added another 381 in its eastern portion two years later. At that time, its maximum capacity was approximately 3,000 residents, all of whom had to demonstrate low- or middle-income status, which amounted to approximately $6,300-9,600 per year, in 1965 dollars. An expansion, Operation Breakthrough East and West, opened in 1973, adding another 464 residential units. Both developments, along with the neighboring LaClede Park, covered about 65 acres and were owned by I.E. Millstone Co. until 1973, and managed by Laclede Town Co. until 1978.

Creating an “urban utopia”

The base goal of the developers of LaClede Town was to replace residents lost during the clearance of Mill Creek Valley. They sought to ultimately create 1700 housing units with a final population of 6000 (Brinkman). By the late 1950s, the city was losing people not only to eviction due to urban renewal, but also to suburbanization. Thus, city officials and developers thought that the construction of new, attractive housing was the key to stemming a dwindling population. James Scheuer, one of the developers of Laclede Park and Laclede Town noted that “the project that we build must justify itself in one to two decades, because it is a hedge on the future of the city” (McCue).

The creators of LaClede Town attempted to attract middle-income–and white–people by offering a unique urban experience. The Federal Housing Administration officials in St. Louis actually asked for an increase in funding for the construction of Laclede Park–the first phase of housing in the area–from headquarters in Washington saying, “the fact that these buildings will be in an area that was formerly a slum will require that the project be overly nice if we are to attract tenants who are able to pay the rents required” (“LaClede Developer”). Though the housing was to be built with federal funding, the developers wanted to distance it from previously built, and currently troubled, public housing projects. Therefore, they planned LaClede Town to “architecturally avoid the sameness and lack of identity” of the high-rise, multi-building complexes as seen at Pruitt-Igoe (“Romney,” Post-Dispatch). Scheuer stated that “we must do more than create conventional, institutional types of buildings. It must become fun to live downtown again” (“LaClede Developer”).

Finally, the planners hoped to create an “urban utopia” by encouraging diversity and integration. According to Berger, Laclede Town was designed “for people who want the chance to relate to others who aren’t exactly like themselves” (Feurstein). The development would attempt be a salve for the increasing racial tensions of St. Louis and the rest of the country.

A New Approach to Public Housing

LaClede Town was designed by architect Chloethiel Woodard “CW” Smith. The buildings themselves were not particularly interesting from an architectural perspective; historians seem to regard them as rather typical for the era – “fairly middling” for the 1960s, according to one scholar (Allen) and a collection of “strange little houses grouped together in an idealist’s dream of community,” as described by one former resident (Udell). But, while the buildings may have been run of the mill, the layout of the development was much more innovative. LaClede Town broke the mold of public housing at the time, particularly fresh on the heels of the demise of nearby Pruitt-Igoe, which by this time had deteriorated and was headed for demolition. Rather than building up, into towers of impersonal apartments, Woodard envisioned a more sprawling living community with character, one that prioritized social space and gave residents a place to gather and celebrate, share life and, for some, raise their families together.

Among Woodard’s most significant uses of social space in LaClede Town was the “The Circle,” a kind of town square, which former residents remember as “the main gathering place of the community. We had Shakespeare, live music, and art fairs there. In the winter plows pushed snow into it. This created a mountain that Santa used for his throne” (Udell). The development also included a barber shop, two laundromats, and a general store, as well as two pubs.

Humans of LaClede Town

The residents of LaClede town represented an eclectic mix of people from diverse backgrounds. It was “a bohemian village of sorts,” according to some observers (O’Neil), with a number of prominent artists, musicians and activists among the owners and tenants. Many were affiliated with local universities, lending an intellectual flavor to the citizenry, which also included people with a wide variety of occupations, from educators to truck drivers, members of the military, engineers, and waiters. There was “even a striptease dancer… she lives next door to the minister,” according to a newspaper report reflecting on the heyday of LaClede Town (Brinkman).

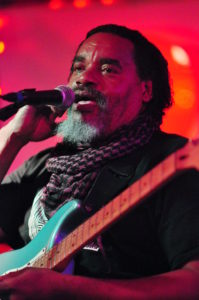

There were some big names in the LaClede Town directory, including prominent social activist Percy Green, who not only lived in the development for some 20 years, but also served as its manager for two stints in the late 1970s into the early 90s. Of the many musicians who lived and likely jammed together in LaClede Town, the one who went on to make the biggest name for himself was probably Ike Willis, who led a successful career as a vocalist and guitarist, playing and touring regularly with Frank Zappa at the peak of his popularity, from 1978 until 1988. Many, like former resident David Udell, never made it to the big time, but remained active in the St. Louis music scene, decades later.

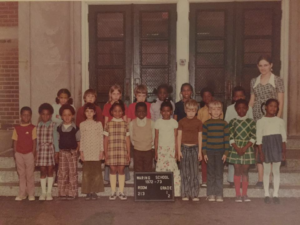

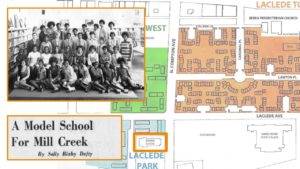

In addition to the “celebrities” of LaClede Town, of course there were plenty of regular folks, including many families who sent their children to Waring School, located right within the boundaries of the community.

When the residents of LaClede Town ultimately dispersed, many seem to have remained in the St. Louis region, with a number of them keeping the memory of their former home alive through a lively Facebook group and an annual reunion, held every August in Forest Park.

“Utopia” achieved

Initially, the creators of LaClede Town, and the city at large, achieved their goals. New residents quickly moved into the cleared Mill Creek Valley area. Only days after the completion of its last building, LaClede Town’s occupancy was 100%. Additionally, the new tenants were diverse. At the height of occupancy between 60-70% of tenants were white, 20-30% were black, and 10% were other minorities, including many immigrants to the U.S. In fact, a 1965 story published in newspapers across the country breathlessly reported that “children of no less than six races play together” (Brinkman).

The new residents were also engaged in the community. “Participation is what LaClede is all about” declared the article in Newsweek (“Urbane”). People of all ages joined together in teams to play baseball, basketball, and softball–one team called the “LaClede Town Losers.” Berger thought that “people forget about things like race when they’re playing games together” (Cooperman). There was a theatre group and an art gallery–which was really just the converted first floor of a townhouse in which the artist-resident had moved upstairs. (Cooperman). Numerous fairs took place in “The Circle” including an annual “Urban Fair” celebrating “the existence of the community” (“LaClede Town”). Spontaneous gatherings, like informal parties or barbeques, also occurred in the many courtyards and fountains. Bob Blackburn, one of the first to move into LaClede Town, said that we “were all attracted by the idea of building a new community. People who didn’t live here came around just to be a part of the ambience…there simply wasn’t anything else like it” (Sweets).

“The Circle” and the Ponderosa General Store

Too hip for a town square, Laclede Town instead had “The Circle” located at Lawton and Cardinal. The Ponderosa General Store gave tenants a small assortment of snacks and household goods to purchase.

The Coach & Four Pub and Towne Tap

The two pubs–The Couch Four and Towne Tap–offered residents a place to mingle after work or sporting events. It was said that at Coach Four one could while away the afternoons listening to Percy Green plan “his raids and demonstrations against the Veiled Prophet Ball” (McGuire).

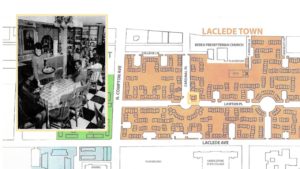

The Circle Coffee House

At 100 Cardinal Pl, The Circle Coffee House was not only a cafe and bookshop, but also the cultural center of the community. The crowd was young and hip and rock bands rehearsed upstairs during the days. Dominic Schaeffer, a former resident, remembers: “As young kids, we could hear them practicing above the Coffee House from the sidewalk…” Every night of the week, except Monday, there was a performance. Young musicians played Jazz, folk, “folk-rock, acid-rock, hard-rock, or whatever-rock” (Sanford). Other times there were plays read aloud or “game theatre” in which the players were chosen from the audience and given a situation to converse about–one of them being “what Hitler saw and said on his first LSD trip” (Sanford).

The Black Artists Group (BAG)

An important component of the early days of LaClede Town was the Black Artist Group (BAG), an artist collective that “…fused ideas of artistic modernism with the local experience of blacks, Afrocentric ways of viewing art, and traditional forms of blues, jazz and narrative expression with social activism and a communal focus” (Looker). They were particularly unique in their blending of various artistic mediums, a novelty at the time. BAG members Oliver Lake, J. D. Parran, Julius Hemphill, Hamiet Bluiett, Floyd LeFlore and his wife, poet Shirley LeFlore, performed regularly” at the Coffee House or in “The Circle” (Schaeffer). Many of the musicians in BAG, who also resided in Laclede Town, gained international success and fame, but were unable to gain traction in St. Louis ultimately moving to Paris or New York.

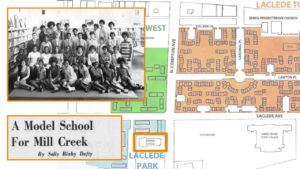

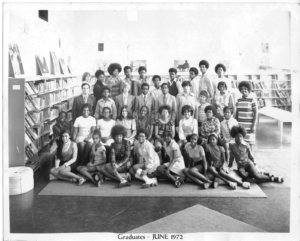

Waring Elementary School

The Waring Elementary School at 25 Compton Ave., was seen as instrumental in attracting families to the nascent neighborhood. Upon the reopening of the school in 1965, The St. Louis Superintendent of Instruction stated that “this school will help determine whether the new town houses and apartments will be inhabited only by childless couples, bachelors and career women or by families with children” (Defty). Waring would be a demonstration school at which teachers and staff were hand-chosen by school officials. Prospective teachers at Harris Teachers College would then observe “the best in action” (Defty). In the late 60s to early 70s, the student-teacher ratio at Waring was the lowest in the city (Wallace).

Berea Presbyterian Church

Located at 3027 Olive, Berea Presbyterian Church was originally founded by freed slaves–though not in this location–and was the only congregation to stay after the Mill Creek Valley clearance. It was one of the first churches in the country to “integrate in reverse;” white people joined the formerly all black congregation. In the words of associate pastor Rev. Paul Smith, the church sought “the binding together of different race and social classes in a new kind of Christian fellowship” (Gottschalk). By day, the facilities were used for nursery, day care and other services and activities for the neighborhood. By night, there were “peace rallies, assemblies to promote racial justice, meetings of political groups, and honor receptions for wounded heroes of the social battles in the streets” (McCarthy). The church was a “central factor in the life of the community around LaClede Town…” and was partially responsible for its success (McCarthy).

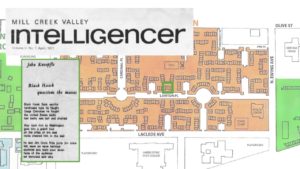

The Mill Creek Valley Intelligencer

LaClede Town had a free and monthly newspaper that covered community news, sports, and theatre, while also printing original literary and visual works from residents. It ran “everything from children’s paper cutouts of the town to translations of Mao Tse-tung’s poetry” (“Urbane”).

Jerry Berger

Jerome “Jerry” Berger Jr is the person most credited for the success of LaClede Town. He was president of Laclede Town Company, the management at Laclede Park, Laclede Town, and Operation Breakthrough from their openings until 1978. Originally from Belleville, IL, he was a member of the beat generation and in his early life occasionally worked as a media writer and disc jockey. He then worked as a manager of a luxury high-rise briefly before taking a position with LaClede Town.

At the beginning of the Town, Berger said that his management company would “go out and recruit a core community that would attract others to come and live there.” He said that they “looked for the boldest most adventuresome [sic] and imaginative people [they] could find” (Feurstein). Once the people were recruited, Berger had four principles for getting them engaged with, or as he called it, “plugged into” the community: First, get the greatest variety of people living together. Second, have places where spontaneous activity occurs like corner stores, bars, coffee houses, pools, laundries, and playgrounds. Third, provide financial and organizational support for activities such as softball, street players, nurseries and daycare, jazz groups, street fairs, and meetings. And lastly, allow outsiders to participate (Montgomery).

An urban renewal success story

Quickly after opening, Laclede Town was praised for being “unique” and “integrated” by local papers and national magazines like Fortune, Architectural Forum, and Newsweek. In 1965 the St. Louis Post Dispatch described LaClede Town as “an alternative to impersonal urban living…” and that it “…is being constructed to recreate the spirit of the old St. Louis townhouses and to bring back a sense of community to the city dweller” (Gottschalk). Politicians visited LaClede Town to gawk at the success of publicly funded, integrated housing. Most notably, then Governor of Michigan George Romney called LaCLede Town “extraordinary” after touring it during his presidential campaign (“Romney”).

The construction of LaClede Park and LaClede Town was also used by the developer, Millstone, as response to those criticizing slow moving redevelopment of Mill Creek Valley. In 1966, Millstone placed an ad in the Post-Dispatch boasting that “once they called it Hiroshima Flats…but look at it now!” (“Once”). “Hiroshima Flats” was the nickname given to the cleared land of the former Mill Creek Valley that sat empty with little development for several years prior. And, of course, the thing to “look at now” was the newly built, and fully occupied, LaClede Town.

Additionally, the success of LaClede Town was used by the press and city officials as justification for the clearance of Mill Creek Valley and for urban renewal in general. A 1968 Post-Dispatch headline declared “Mill Creek Valley: Slum to Showcase” splashing on the page a large picture of two boys, one white and one black, playing in the LaClede Town circle (Adams). Another article in 1970 termed the “Mill Creek Job” as “nearly complete” and “a great success” praising the LaClede Town developments as “high-density and high-return” (Evans).

Further, LaClede Town was frequently juxtaposed with and, for many, was the antidote to the failure of Pruitt-Igoe. In 1974, a letter was published in the Post-Dispatch by the St. Louis Regional Commerce & Growth Association as a curious attempt to bolster the city. It stated, “We should be and are concerned about the failure of Pruitt-Igoe. But why forget about the outstanding success of Laclede Town” (Saint Louis). Also, some officials from the Federal Department for Housing and Urban Development proposed demolition of the infamous high-rise public housing and the “construction of a LaClede Town-Type project of townhouses” (HUD).

The Decline of LaClede Town

It would later come to light that throughout the first 10 years of LaClede Town, the owner, Millstone Construction, was supplying an enormous amount of funding to the development. At $750,000, adjusted for inflation, per year, this money was in addition to collected rents. “We certainly did subsidize it,” Millstone would later say, “it nearly bankrupted us, as we poured profits from Millstone Construction into LaClede Town” (“What”). He decried that HUD would not let Millstone charge tenants extra for security or trash collection and that the city would not supply these needed services because they considered LaClede Town as a private development (“What”).

In 1973, Millstone sold Laclede Park, LaClede Town, and Operation Breakthrough to a new owner, Laclede Associates, who were less likely to pay for necessary maintenance. In 1976, with the economy tightening and a conservative federal government cutting assistance programs, the management, LaClede Town Co., was forced to request a rent increase. The tenants balked and appealed to HUD to deny the request. HUD sided with the residents, blocking the rent increase finding “irregularities in LaClede Town’s accounting practices” as well as “excessive operating costs” (“Rent”). These events led to HUD’s first ever audit of LaClede Town since being built.

Ultimately, HUD found that between 1973 and 1976, LaClede Town Co. was operating in a $600,000 deficit with over $1 million in uncollected rent. The Feds also found that management had left apartments empty for months while reporting no vacancies and also not charging the proper value for rent, often asking for too little relative to tenant’s income.

During this period, maintenance also began to several lack. In 1977, a Post-Dispatch article reported that weeds and grass grew waist high, paint was peeling, shutters and balconies were falling down, and playground equipment was broken and sandboxes were polluted with broken glass and stagnant water. There were also problems with plumbing, erosion, and piling trash. The paper reported that “where once there were good times and happy residents, there now is dissatisfaction, dissection and fear” (Lawrence).

Further problems arose when management was accused of bias in tenant selection. In 1978 two government agencies, the Missouri Commission on Human Rights and the Equal Opportunity Division of HUD, found “probable cause” to believe that LaClede Town had discriminated against a black woman by refusing her an apartment (Obika). In a homemade sting operation, the woman had been told that there were no vacancies and then moments later, her friend, a white woman with similar income, had been offered an apartment immediately.

Top U.S. And city officials continued to push for maintenance issues to be fixed and finally, in the Fall of 1978, HUD removed Jerry Berger and Laclede Town Co as managers after more than 14 years of operation. In 1983, a Post-Dispatch article remembered that Berger’s “fiscal controls were somewhat loose…[he] is remembered more for his entertaining personality than for being a prudent businessman” (Malone).

By 1975, those with means–primarily those who were white–were moving out leaving only the poor and black–as well as the associated stigma. The developments went through a series of management corporations and rent increases and even a rent strike in 1980. By 1985, $5 million was spent by the then owner on renovations, but it would be too little, too late as vacancy, drug, security, and maintenance problems, due to a lack of consistent funding, beleaguered the developments.

By 1990, LaClede Town was 60% vacant. By 1991, it was 70%. HUD finally took ownership in 1991. Several plans were floated as to what to do with the troubled Town including renovation into tenant-owned condos or complete replacement with new residential or commercial. Finally, in 1995, HUD began demolition of LaCLede Town. There were still 200 tenants living there with one, Mattie Trice, quoted as saying “I’m very upset and angry, but there’s absolutely nothing I can do about it but fume” (Gross). HUD would eventually sell the land to the city.

Without A Trace

Visiting the LaClede Town site today, there are no visible signs of what was once here. When the buildings were torn down, some of the property was redeveloped, but much has remained vacant. In 2000, biotechnology company Sigma-Aldrich invested $55 million to build a 145,000-square-foot biotech research facility on the southeast corner of the site. The complex features office and lab space for 220 research chemists and a 300-seat auditorium, and is situated where LaClede Town’s tennis court and health center had once stood.

Neighboring Saint Louis University and Harris-Stowe State University also claimed some of the land, with Saint Louis building its enormous athletics complex, the Chaifetz Arena, at the same address that once belonged to Waring School; and Harris-Stowe expanding its academic and residential facilities on the sites where homes, businesses, and gathering spaces had once stood.

Many of the roads that once ran through LaClede Town are now blocked off, making a literal trip down memory lane physically impossible. It seems the legacy of LaClede Town will have to exist in the reunions, relationships, and memories of those who lived, worked, and played in LaClede Town; much like Mill Creek Valley, there is very little evidence left where this once unique place stood.

We tore down the messy and chaotic tenements of Mill Creek Valley, home to 6,000 mostly black and low-income St. Louisans, to build neat and tidy townhomes for half the number of middle-income and diverse, but mostly white, new St. Louisans. Many former residents of a certain age look back with fondness at those early days, and perhaps rightly so. The stories do make LaClede Town sound utopian. However, the story of LaClede Town would be incomplete without also acknowledging the residents who lived there during the development’s period of decline, and had a very different experience.

For better or worse, LaClede Town’s legacy is one of hope and optimism, as well as of neglect and, ultimately, defeat. It offers significant lessons about housing, race, and public policy, and should serve as inspiration – and a cautionary tale – for anyone who might venture to create their own version of an urban utopia.

Works Cited

Adams, Robert. “Mill Creek Valley: Slum to Showcase.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 22 Dec. 1968:

- Print.

Allen, Michael. “Laclede Town Remembered.” Preservation Research Office. N.p., 18 Oct. 2009.

Web. 01 May 2017.

Brinkman, Grover. “St. Louis’ LaClede Town Unique Housing Program” Xenia Daily Gazette 26 Nov.

1965: 11. Print.

Cooperman, Melvin. “A Good Place to Live…” Laclede Town Company Management Manual,

prepared by LaClede Town Company, 1972, Appendix 14.

Defty, Sally Bixby. “A Model School for Mill Creek.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 23 Feb. 1965: 38.

Print.

Evans, E.S. “Mill Creek Job, Nearly Complete, is Acclaimed as Great Success.” St. Louis

Post-Dispatch 12 July 1970: 1. Print.

Feurstein, Ruth. “Unusual Area Integrated in All Ways.” Anderson Herald [Anderson, IN] 15 Mar

1967: 6. Print.

Gottschalk, Earl C. “Mill Creek Valley to Celebrate Its Rebirth.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 28 July

1965: 3. Print.

Gross, Thom. “Most of LaClede Town to be Leveled.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 20 Jan. 1995: 1.

Print.

“HUD Will Not Approve New Pruitt-Igoe Plan.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 2 June 1972: 33. Print.

“LaClede Developer Assails GAO for Criticizing FHA Loans.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 31 Oct.

1963: 33. Print.

“LaClede Town: The Most Vital Town in Town” Laclede Town Company Management Manual,

LaClede Town Company, 1972, Appendix 15.

Lawrence, Ronald J. “LaClede Town Maintenance Criticized.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 18 Sep.

1977: 1. Print.

Looker, Benjamin. “‘Poets of Action’: The Saint Louis Black Artists’ Group, 1968-1972.” All

About Jazz. All About Jazz, 19 Dec. 2004. Web. 24 April 2017.

Malone, Roy. “LaClede Town: Boom to Bust in 10 Years.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 16 Oct. 1983:

- Print.

McCarthy, Jake. “Religion In The Streets.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 21 May 1973: 3. Print.

McCue, George. “New Concepts Used in Housing In Mill Creek Valley; Social Centers Planned

for Residents.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 5 Sept. 1962: 33, 50. Print.

McGuire, John M. “Farewell to Utopia.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 12 Feb. 1995: 39, 46. Print.

Montgomery, Roger. “Swinging LaClede Town.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 9 Jan. 1968: 10. Print.

Obika, D.D. “Two Agencies Find Probable Bias in Rental Turndown at LaClede Town.” St. Louis

Post-Dispatch 5 June 1978: 27. Print.

O’Neil, Tim. “A look back: Clearing of Mill Creek Valley changed the face of the city.” St. Louis

Post-Dispatch 9 Aug. 2009. Web. 3 Apr. 2017.

“Once they called it Hiroshima Flats…but look at it now!” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 8 May 1966:

- Print.

“Rent Hike Denied at LaClede Town.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 23 Sept. 1976: 3. Print.

“Romney Praises LaClede Town, Council House.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 20 Sept. 1967: 3.

Print.

Saint Louis Regional Commerce and Growth Association. Letter. St. Louis Post-Dispatch 21

April 1974: 200. Print.

Sanford, Robert. “Hippie Here has 2 Jobs and 6-Room Townhouse.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 17

July 1967: 9. Print.

Schaeffer, Dominic. “Laclede Town: Impressions of a Native Son.” The Commonspace.

The Commonspace, Oct. 2003. Web. 24 April 2017.

Sweets, Ellen. “The Late, Great LaClede Town.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 30 Nov. 1997: 41, 48.

Print.

Udell, David. “Laclede Town.” My St. Louis. N.p., 14 Feb. 2009. Web. 01 May 2017.

“An Urbane Human Stew.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 30 March 1968: 4. Print.

Wallace, Linda S. “Parents Trying to Revitalize Waring School.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 3 Feb.

1977: 74. Print.

“What Went Wrong?” St. Louis Post-Dispatch 12 Feb. 1995: 39. Print.