By Christine Qu

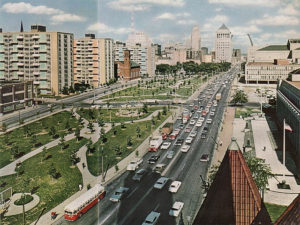

When we think of the White modernist ideals, we think of something like this

(retrieved from nextstl.com)

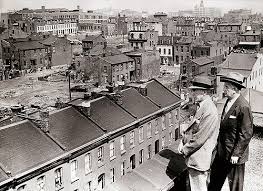

photo. Modern architecture and city landscape should have some of the qualities such as brand-new, clean, efficient, and the look or pattern of it should be somewhat universally applicable. Therefore, something like this – the Mill Creek

(retrieved from nextstl.com)

Valley obviously did not fit into that narrative. And for White male elites like Mayor Tucker, it had to go: “Mill Creek Valley … had decayed into 100 blocks of

(retrieved from http://amcs.wustl.edu)

hopeless, rat-infested, residential slums.”[1] Further, when we look closer at this photography, it positions these two White male elites – Mayor Tucker and civic leader Sidney Maestre as “visionary symbols of progress,” the neighborhood as “inhuman and inhumane.”[2]

They never cared about the perspective from the other side. What did the black residents think? Did they see their neighborhood as nothing but a hopeless slum? Or even, what kind of a place do they want to live in?

Located on the corner of Jefferson and Market, Peoples Finance Building was one of the landmarks of Mill Creek Valley. It was the center of African American political, social, and commercial life for three decades,[3] and therefore had significant symbolic and social meanings to the black community.

As a symbolic space, first of all, it was the first commercial building in the U.S. built entirely by black money, and its formal opening attracted a crowd of more than 5,000. Its Peoples Finance Corporation was allegedly the “largest finance company among Negros in the world.”[4] With 81 offices, an assembly hall, a rooftop garden, and seven stores,[5] it carried such cachet that many black St. Louisans still remark, “Anybody who was anybody had his office in the Peoples Finance Building.”[6] They include most of the St. Louis branches of black national organizations such as NAACP, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the Colored Motion Picture Operators, the Missouri Pacific, Wabash, the March on Washington unit, and black papers such as the St. Louis Americans, and St. Louis Argus. In short, “for African Americans, Peoples Finance was a ‘race enterprise’ representing the fulfillment of black aspirations and a monument of black achievement.”[7]

As a social Space, Peoples Finance was known as “the Hub” of black political activity in St. Louis – “In its heyday, the Peoples Finance Building hummed with activity and purred like a well-fed cat.”[8] Throughout the 1940s the Peoples Finance Building was “the scene of scores of gatherings, official and informal, where civil rights strategies were discussed and implemented.”[9]

The proximity of leaders in the community and membership institutions fighting for change developed into a brain trust where an almost daily cross-fertilization of ideas was unavoidable. These exchanges were assisted by the Deluxe Restaurant, situated directly across Jefferson Avenue … It was one of the few restaurants where Negros could sit down for a meal and be served in St. Louis, and the Finance Building’s tenants usually streamed across the street for lunch. Professionals, civil servants, and blue-collar folk alike came there from downtown and across Jefferson Avenue, turning it into the Negro equivalent of a golf course’s nineteenth hole where deals were brokered and talk was valuable. If you wanted to know wha was going on, you went there and listened. The tables were big, and people just sat down wherever there was a free chair to join in on conversations always worth their time.[10]

This “hopeless” slum in the eye of White elites sounds to me like a perfect example of Habermas’ ideal public sphere.

Moreover, “The Peoples Finance Building was crowned by a dazzling penthouse ballroom, and no invitation to one of its events ever went begging.”[11] From the 1929 Alpha Kappa Alpha gala to the Royal Vagabonds in 1932, its grant events are still remembered in the heart of middle-class black St. Louisans even to this date.

Today, all the traces are erased. Standing at the very spot where Peoples

Finance used to be, we do not see any memorials or marks of it left.

The point of the project is not that Mill Creek Valley did not have any problems. My argument is this: the demolition of Mill Creek Valley is essentially about power and hegemony. It’s not just about whose voices mattered in the decision. It’s also about whose values mattered? Who gets to set the “norm” of what a neighborhood should look like? Whose standard gets to be the standard, and to judge the others’ and tell them your neighborhood is worthless? And who has control to decide and plan for our lives and our future?

Footnotes:

[1] City Plan Commission, “History of Renewal,” retrieved from urbanreviewstl.com

[2] Jonathan Karp, “Exploring the Challenges of Representing Sites with Images,” Material World of Modern Segregation blog, amcs.wustl.edu

[3] 250in250.Mohistory.org

[4] Ibid.,

[5] Ibid.,

[6] Gail Milissa Grant, At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 150

[7] 250in250.Mohistory.org

[8] Gail Milissa Grant, At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 153

[9] Ibid., p. 159

[10] Gail Milissa Grant, At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 152

[11] Ibid.,

At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 150

[7] 250in250.Mohistory.org

[8] Gail Milissa Grant, At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 153

[9] Ibid., p. 159

[10] Gail Milissa Grant, At the Elbows of My Elders, 2008, p. 152

[11] Ibid.,