By Ashley Holder and Molly Calvo

Intro

In his 1960 book The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch argues that the city is not a thing

but instead an object of collective perception. His thesis seems particularly relevant in the 1 context of mid-century urban renewal projects, which demolished large swaths of the city, leaving little more than collective memories to replace entire neighborhoods. In 1954, St. Louis Mayor Raymond Tucker mandated that the Mill Creek Valley, a working-class African-American neighborhood, be slated for clearance, obsentibley as a response to deteriorating conditions which classified the area as “blighted”. Over the next decade, nearly 6,000 buildings were demolished, leaving few remnants of the community’s history behind. Land clearance as a strategy to address poverty has been a common discourse in the history of St. Louis, which has made rare the representation of historical events and narratives. Several buildings were preserved during the clearance, some for reasons more obvious than others. These

extant buildings serve as critical tools in piecing together Mill Creek’s history, though today they are generally valued more for their distinct aesthetic qualities, or as Lynch terms it,“imageability”, the attributes of an object that make it distinct and memorable. This paper 2 examines four of Mill Creek’s remaining buildings to uncover their lost history and understand how their history is being remade in the present.

Vashon High School

The former Vashon High School Building remains one of the largest physical remnants of the Mill Creek Valley, though today it blends in among the collegiate architecture of Harris Stowe State University. The Plessy v. Ferguson court case in 1896 made “separate but equal” segregation legal in the United States, which included segregating public schools. Sumner High School in the Ville neighborhood was the only public high school for African-Americans in St. Louis until Vashon High was established in 1927 to serve the Mill Creek Valley, relieving overcrowding at Sumner. The school was largely made possible by the 3 diligent advocacy of African-American parents, who filed lawsuits lobbying for more schools as Sumner became more crowded.

In its heyday, Vashon was a “brand-new, beautiful building” where many of the teachers had PhDs. However, amongst the African-American community, Sumner High was generally 4 considered to be a better school because the students from the Ville neighborhood were generally wealthier than in Mill Creek, and many Vashon teachers themselves lived in the Ville. A former student recalls that it was always exciting for Vashon to beat Sumner in football as a way for the school to prove itself. Despite facing discrimination and segregation from whites across the 5 board, the St. Louis’s African-American community did place significant importance on income and social class, which separated the Ville and Mill Creek communities. The modern facilities and qualified faculty of Vashon High School allowed Mill Creek Valley students the opportunity to receive a good education in their own neighborhood rather than traveling to a more prosperous one. Several Vashon alumnae went on to Stowe Teacher’s College and returned to the community to teach. In 1936, a Vashon graduate named Lloyd Gaines applied to the whites-only law school at the University of Missouri and was rejected, he sued the school in a case that went

to the United States Supreme Court but ultimately resulted in the creation of a separate law school for African-Americans rather than integration of the University of Missouri. As the 6 neighborhoods’ only public high school and one of just a few high schools for African-Americans in St. Louis, Vashon served a critical role in the Mill Creek Valley, not only for education but also for bringing together the community. The demolition of the Mill Creek Valley in the 1960s devastated that community, forcing Vashon High School to move elsewhere to retain its students.

Today, the Vashon High School building continues to serve the St. Louis community as a part of Harris Stowe State University, while remaining a crucial piece of Mill Creek Valley history. Harris Stowe, which began as two segregated teacher’s colleges but eventually integrated and expanded to offer more degrees, is a Historically Black University, meaning that the Vashon building continues to serve Missouri’s African-American community. Harris-Stowe appears not to emphasize the history of the building, as there is no information about its original function on their website and it has since been renamed to honor the university’s former president. Surprisingly, the St. Louis Public Schools website features a relatively lengthy history of Vashon which recounts the devastating effects the clearance had on the community. The website recalls the ways that Mill Creek parents and students were blindsided by the sudden clearance which forced them out of their homes. This straightforward assessment of the 7 clearance is unusual for a government-sponsored website, as the city of St. Louis has done little to acknowledge the full scale of clearance or commemorate lost African-American history.

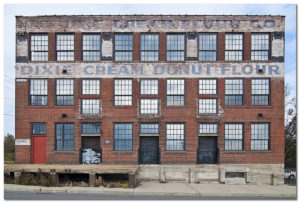

Dixie Cream Donut Flour

Notable as one of the few remaining vernacular buildings left in the Mill Creek area, the red brick building at 2213-19 Scott Avenue has been a location of industry and commerce since the early 20th century. The building housed various flour companies including Stanard-Tilton Milling Co until Dixie Cream bought the building in 1946, giving the building the paint job it retains today. For several decades the building

was one of only two manufacturing plants for Dixie Cream in the country, producing

ingredients for the bakery chain’s more than 200 locations nationwide. Eventually Dixie Cream downsized and moved elsewhere, but the building became a storage facility for Imperial Flour Co, though it suffered a fire and a partial collapse between 1989 and 1993. The building was then rehabbed to house a local vanilla company before being purchased in ? by Arch Reactor, a St. Louis based “hackerspace” which provides tools and facilities for individuals in tech and

creative fields. Before the clearance, the Dixie Cream building sat at the edge of a dense urban neighborhood, as evidenced by Sanborn fire insurance maps. The rectangular street grid depicted in the Sanborn maps contrasts sharply with the site’s current siting in an awkward patch between an on-ramp for I-64 and a wide expanse of train tracks. Fragments of the original street grid exist slightly north- 22nd and 23rd streets, which mark the boundaries of the page of the Sanborn map, were severed by the highway, but they remain in small stretches intersecting with Market Street near the FBI campus. What remains of Scott Avenue has lost its pedestrian appeal, stringing together large scale warehouse type facilities which dwarf the century-old Dixie Cream building. Despite its relatively isolating location, the building remains on the mind of St. Louisans because it sits facing the Metrolink train tracks where its large painted lettering reading “Dixie Cream Donut Flour” are clearly visible. The red brick building and faded paint job evoke immediate nostalgia amidst the low, grey warehouses built in the modern era. No longer efficient for factory production, the building is now valued for the same reasons it would have been scorned during

the mid-twentieth century- for its shabby industrial aesthetics that provide a glimpse of the historic past of the Mill Creek Valley site.

In a paper for the 2014 Mediated City Conference, Nicholas Balaisis explores the

phenomena of the reappropriation of industrial sites, particularly those once targeted for urban renewal, in which the interior of a building is remodeled while the exterior is preserved, “making the building’s former history a prominent part of the building’s new identity”. The concepts 8 evoked by early 20th century industrial aesthetics pair well with the goals of a makerspace such as Arch Reactor because both emphasize personal physical labor and reject the effects of global manufacturing. Furthermore, Balaisis notes, renovations of industrial buildings are generally linked to an effort to create “live/work clusters” because of their associations with a time when this type of lifestyle was the norm. Of course, the Mill Creek Valley was once a “live/work 9 cluster” before it was demolished to make way for giant corporate campuses and a highway that

funnels people from where they live to where they work. The designation of functioning neighborhoods where people both lived and worked as “slums” and subsequent clearance of these vibrant communities created a city full of empty spaces where people no longer wanted to live. Arch Reactor’s unfortunate siting makes it an unlikely location for the reestablishment of a “live/work cluster” but the renovation of an industrial building into a tech/creative space is indicative of general trends in urban redevelopment. Additionally, the makerspace/hackerspace concept is part of a larger trend in tech that some say will invigorate St. Louis by drawing more young people back into the city. 10

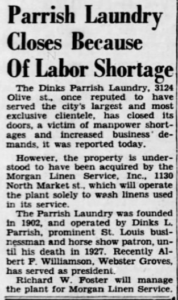

Dinks Parrish Laundry Building

The Dinks Parrish Laundry building is an example of distinct architecture that would have stood out from the typical rowhouses of the Mill Creek Valley. Designed in 1916 by prominent Jewish architect William Levy, the building did little to recognize its surroundings, which were far humbler than the ornate structure clad in terra cotta. This allusion to architecture that was distinctly non-local could have been because it was meant to serve a cosmopolitan clientele that would have been attracted to the buildings allusions to European architecture. The building was

commissioned by Parrish to house his laundry business, which had been growing since 1902 in a different location. The new building on Olive St. was less accessible to his advertised clients, who tended to be upper class white men and women. Despite this, his laundry service continued to thrive, offering cleaning services for handkerchiefs, silk umbrellas, “Genuine Imported Guyot Suspenders”, and even canes. His laundry service, while in the Mill Creek Valley, appears to 11 have been very much detached from the working-class, black community that surrounded it. Both the building and the business catered to an upscale white crowd, advertising this architecturally in the ornamented European style, visually in newspaper advertisements, and by targeting a wealthy white customer base. It is possible that the building’s visual appeal, as well as its relationship to white St. Louis, allowed it to remain untouched during the Mill Creek

Valley clearing.

Since Dinks Parrish Laundry closed in 1943, the blue and white building at 3821 Olive Street has housed a variety of establishments. Morgan Linen Co, a smaller business that primarily laundered towels, moved into the space during World War II, serving members of the military as well as the surrounding community. Morgan Linen could expand their customer base without needing to increase employment because of the less extensive nature of the laundering. In the early 2000s, the building was

repurposed as a mixed use building with apartments and a nightclub, called The Loft Jazz Club but having little to do with jazz. The club’s marketing appears to target African-Americans, which is significant because of the ways that the building in its previous iterations catered to white patrons. The club has since closed, making way for a new business called the Center Ice Brewery, advertised as a space for hockey-loving beer drinkers. Articles about the renovation of the space mention the owner’s desire to incorporate hockey memorabilia into the design, particularly salvaged material from

the old hockey stadium, which was demolished in 1999. By doing so, the 12 bar’s owner, a lifelong Blues fan, hopes to preserve his memories from going to games in the old stadium near Forest Park by bringing them to a new site, a concept that

evokes comparison with the ways that narratives from the Mill Creek Valley have been preserved or destroyed. There is no space with salvaged materials from the Mill Creek buildings, nor is there a place where memories of the place have been preserved, other than in oral histories. Furthermore, hockey’s associations a white-dominated sport (only 5% of NHL players are black) imply that the space will cater to a mostly white clientele, as Dinks Parrish Laundry did over half a century ago. Dinks Parrish Laundry has found its place as a facade- both 13 architecturally and culturally. The building, though beautiful, did little for the Mill Creek Valley community during the Dinks Parrish Laundry period, and will continue to serve a customer base

that likely does not live in the neighborhood. The ornate aesthetics of the building allow it to be separated from the working-class Mill Creek narrative, creating a space that exists in a liminal space between cultures and time periods.

Berea Presbyterian Church

The Berea Presbyterian church was built in 1929 after the founding of Berea Congregation in 1887 by Mary Jane Townsend. The congregation was formed after African-Americans were expelled fro Washington-Compton Presbyterian Church, leading to the founding of the first African-American Presbyterian

church west of the Mississippi River.14 Like Vashon High School, Berea was a community hub of the Mill Creek Valley, offering sports teams along with typical religious activities. It is unclear why the church was saved from clearance, but it was the sole survivor out of over 40 churches that had once been in the neighborhood. The church remained active during clearance and even managed to purchase an acre of land from the Land Clearance Redevelopment Authority for an expansion.

The church’s maintenance was due to efforts from its committed leader, Reverend Carl S. Dudley, who vowed to maintain the church’s presence despite the displacement of its congregation. The building of Laclede Town in the 1960s brought a community back to Berea, 15 and the site was used as a location for Civil Rights activists to meet. When Laclede town was cleared the church once again lost a significant portion of its congregation, but remained active into the 21st century, demonstrating that it was a crucial component of community for present or former neighborhood residents.

When the church was one of 40 in the dense Mill Creek Valley it was simply an

important community space, when it was one of only a handful of buildings left standing in a 200-acre wasteland it became iconic. Today, the church gets very little of the recognition it deserves as a space for those that fought for equal rights for decades, from Mary Jane Townsend to local civil rights leaders. After being purchased by Saint Louis University, the church was rebranded as “Il Monastero” banquet center, offering a venue space for a variety of events. The generic Italian name not only neutralizes the church’s place in the fight for racial justice but it takes the building firmly out of the St. Louis context by alluding to European history, just as William Levy did when he designed Dinks Parrish Laundry. Without something to commemorate what happened there, the site may fade into oblivion, and the history of Mill Creek’s last church will be lost.

Conclusion

Today, a hodgepodge of buildings is all we have left of the built fabric of the Mill Creek

Valley. The histories of these buildings reveal that there is no easy way to classify why certain buildings were saved and others demolished. It is safe to assume that Vashon High School was preserved because of its monumentality, and the Dinks Parrish Laundry because of its ornate architecture, but the question remains why one particular church and one particular factory were preserved while dozens of other churches and factories were destroyed. The preservation of the Dixie Cream Donut Flour building is particularly important because it is an example of vernacular architecture, which Dolores Hayden emphasizes in The Power of Place is crucial to understanding how everyday people lived and worked. It is notable that two of our sites (Berea 16 and Vashon) deal specifically with African-American history while the other two (Dixie Cream and Dinks) are more ambiguously linked to the community. Both companies were white owned, but may have employed African-Americans who lived nearby. Themes of historical erasure thread all of the sites together, though there seems to be a delicate balance between deliberate erasure and simply repurposing sites. For example, the renovation of Dinks Parrish Laundry to a craft brewing company in the present day appears to be an example of repurposing–the beautiful building has housed several businesses, and the laundry had very little connection to the community–while the conversion from Berea Church to an event space is more troubling because the church’s significance to the Mill Creek community is not only being ignored but actively erased. As Mill Creek residents age, these buildings may be all we have left to tell the story of the thriving community that once inhabited them, making preservation of them and their historical narratives all the more important.

Footnotes:

1 Lynch, Kevin. The Image of the City. MIT Press, 1960.

2 Wesley, Doris A., Wiley Price, and Ann Morris. Lift Every Voice and Sing: St. Louis

African-Americans in the Twentieth Century : Narratives. N.p.: University of Missouri, 1999.

3 Ibid.

4 Wright, John Aaron. Discovering African American St.Louis. N.p.: Missouri History Museum,

2002.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 “A History of Vashon High School.” St. Louis Public Schools.

http://www.slps.org/domain/2956.

8 Balaisis, Nicholas. “Factory Nostalgia: Industrial Aesthetic in the Digital City”. Mediated City Conference, Los

Angeles CA October 2014.

9Ibid.

10 Yoegurst, Joe. “St. Louis and Kansas City Bounce Back.” CNN. Last modified February 16, 2017.

11

“Dinks Parrish Laundry”. St. Louis Post Dispatch [St. Louis] 08 Dec 1919

12

“Center Ice Brewery to Open in St. Louis in 2017”. Feast Magazine, August 4, 2016.

13 Judd, J. Wesley. “Why the Ice is White.” Pacfic Standard, June 19, 2015.

14 “Pastor Finds Strength in Story of Historic Church’s Founder”. St. Louis Post Dispatch [St.

Louis] 10 March 2001: page 14

15 St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “Talk of Mill Creek Church of Future.” January 5, 1963.

16 Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History.

Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1995